Guest Contributor: Dr. Robert Besseling, Executive Director of EXX Africa

The onset of the coronavirus in Africa has not reached the calamitous public health crisis that many analysts had initially forecast, even though there are ongoing debates over the accuracy of statistics, limited testing capacity, and important regional variations. But most analysts agree that COVID-19 has not yet fully hit the world’s most vulnerable continent and the next few months will be critical for many African countries as they deal with the pandemic.

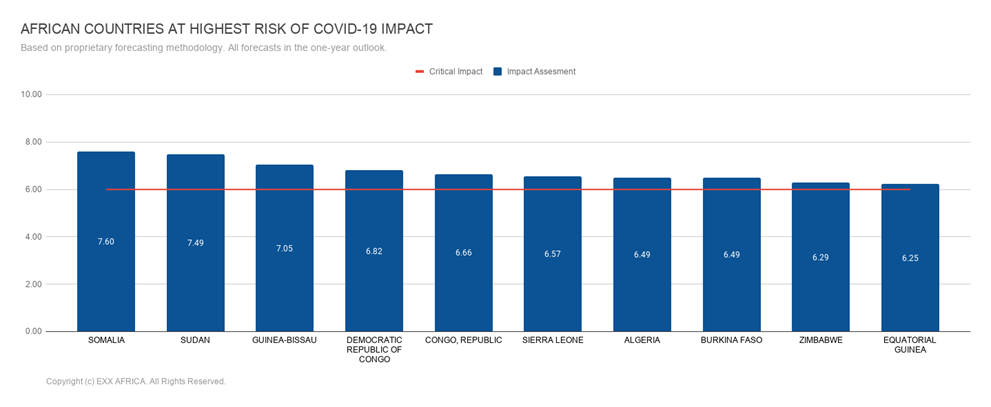

In the meantime, the economic repercussions of lockdowns, smaller global trade flows, and supply chain disruptions are causing a more significant backlash that imperil political stability and economic resilience in some of the poorest countries on Earth. EXX Africa’s COVID-19 country risk vulnerability model forecasts that unstable states such as Sudan and DRC, as well as fragile economies like Sierra Leone, are most exposed to the longer-term implications of the pandemic.

Multilateral institutions have taken the lead in supporting Africa’s response to the crisis, by quickly releasing funds for public healthcare and economic stimulus. Long-time sceptics of the Bretton Woods institutions, such as South Africa and Nigeria, have readily accepted IMF financial assistance, although such aid comes with few structural adjustment and transparency conditions. Other major economies like Egypt have returned to a formal programme with the Fund, which does include such conditionalities and will resume market-based reforms.

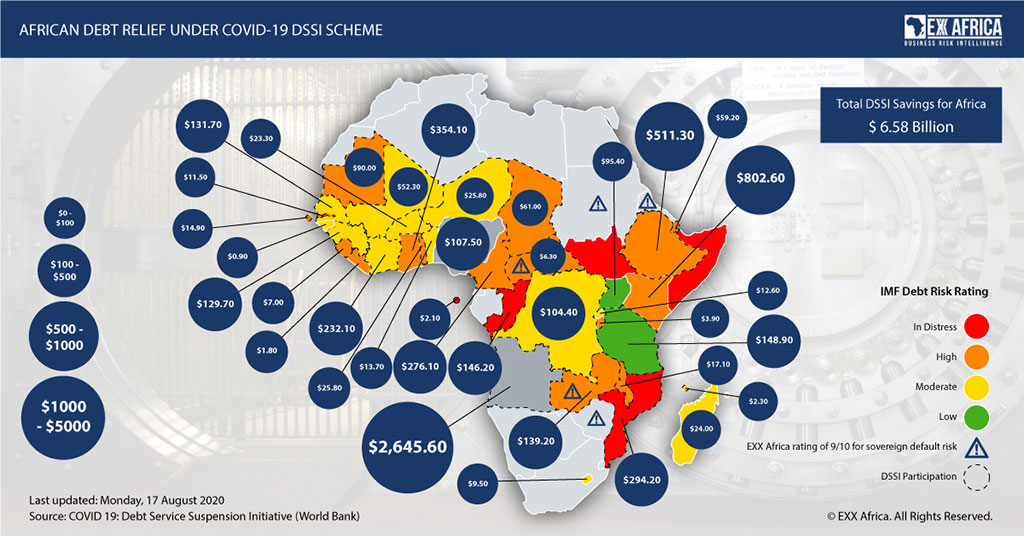

However, the G-20 debt service suspension initiative will not be sufficient to stave off a wave of defaults on interest and capital repayments towards the end of 2020 and beyond. Countries like Zambia and the Republic of Congo are set to join long-time arrears offenders, such as Zimbabwe and Sudan, as state revenues dry up and local currencies collapse. To avoid such a scenario, much broader debt relief will be required to encompass commercial creditors and China; although such a prospect seems unlikely in current conditions.

Looking beyond the doom and gloom, for some smaller and more diversified markets that have long embraced foreign investment and reform, such as Senegal, Benin, and Rwanda, the economic impact of the pandemic will be limited and a swift recovery remains probable in 2021.

The crisis has also created fresh investment opportunities for some sectors, such as renewable energy and public healthcare investment, which have long been desperately needed on a continent that thrives on coal and oil, with often mediocre public health infrastructure. Foreign investors will find ample return on such projects and governments need to collaborate to ensure political risks are mitigated.

Africa’s largest economies with lacklustre economies and entrenched interests will also need to move towards reform. South Africa’s debt-burdened state-owned enterprises require a shake-up, while Nigeria needs to proceed with oil sector restructuring before issuing more production licenses. The key question is whether Africa’s disparate states can collaborate on battling the coronavirus, embrace economic reforms, and boost intra-regional trade by reigniting the process towards creating the world’s largest free-trade zone. Perhaps, the current crisis offers the most valuable opportunity to reshape Africa for generations to come.